Caterina Tiazzoldi è un architetto, interior e uno strategic designer. Dopo aver conseguito un Master of Science in Architectural Design presso la Columbia University, ha avuto l’onore di essere selezionata per partecipare alla 17ª edizione della Biennale di Venezia (2021) nella sezione Resilient Communities del Padiglione Italia. Tra i riconoscimenti ottenuti, figurano il Premio Architetture Rivelate e la nomina a finalista del Premio Renzo Piano per Giovani Architetti Italiani.

Il suo lavoro si focalizza sulla contaminazione tra architettura, scienza e innovazione sociale. Nello specifico nella progettazione di spazi per uffici coworking, retail, rigenerazione urbana ed arte pubblica. Ha insegnato presso istituzioni prestigiose come la Columbia University, il Politecnico di Torino e la Rhode Island School of Design. Inoltre, per oltre 15 anni, ha co-fondato e diretto il centro di ricerca Non-Linear Solutions Unit (NSU) presso la Columbia University, in collaborazione con il Politecnico di Torino.

Caterina Tiazzoldi is an architect, interior designer, and strategic designer. After obtaining a Master of Science in Architectural Design from Columbia University, she was selected to participate in the 17th edition of the Venice Biennale (2021) in the Resilient Communities section of the Italian Pavilion. She has received the Architetture Rivelate Award and has been named a finalist for the Renzo Piano Prize for Young Italian Architects.

Her work focuses on the intersection of architecture, science, and social innovation, particularly in the design of coworking office spaces, retail, urban regeneration, and public art. She has taught at prestigious institutions such as Columbia University, Politecnico di Torino, and the Rhode Island School of Design. Additionally, for over 15 years, she co-founded and directed the Non-Linear Solutions Unit (NSU) research centre at Columbia University in collaboration with Politecnico di Torino.

Il tuo studio ha uno staff completamente al femminile? Perché questa scelta?

Nel mio caso, poiché non si tratta né di uno studio associato né di un collettivo, la questione del genere non assume rilevanza. Sono semplicemente una donna, ed è così che è stato. Ho collaborato con persone di grande valore, sia uomini che donne.

Non nego che, nei cantieri per negozi o installazioni rapide, dove la manodopera spesso proviene da contesti culturali, religiosi o tradizionali molto eterogenei, non ritengo utile condurre battaglie dirette per la parità di genere. Tuttavia, riconosco che in molte situazioni la presenza di un uomo può rassicurare le maestranze.

Un episodio interessante riguarda una strategia che ho adottato, simile a quanto mostrato nel film Scusate se esisto! di Riccardo Milani. In alcuni cantieri, ho collaborato con un collega uomo, anche lui gay, per interagire con i fornitori. Anche nel mio caso, questa dinamica si è rivelata molto utile in molteplici situazioni. Devo ringraziare la mia amica Valerie Viscardi editor presso Louis Vuitton e poi indipendente di avermi aiutata a capire come raggiungere i giornalisti senza passare dalle agenzie di stampa.

Does your studio have an all-women team? What inspired this choice?

Since I’m neither part of an associated practice nor a collective, the issue of gender doesn’t hold much relevance. I’m simply a woman, and that’s how it’s always been. I’ve collaborated with incredibly talented people, both men and women. An interesting episode concerns a strategy I adopted, similar to what’s portrayed in the movie Sorry to Exist? by Riccardo Milani. On some construction sites, I worked alongside a male colleague, who also happened to be gay, to interact with suppliers. In my case, this dynamic proved to be highly effective in various situations.

I won’t deny that, in construction sites for shops or rapid installations—where the workforce often comes from highly diverse cultural, religious, or traditional backgrounds—I don’t find it helpful to engage in direct battles for gender equality. However, I acknowledge that, in many situations, the presence of a man can reassure workers. I have to thank my friend Valerie Viscardi, editor at Louis Vuitton and then independent, for helping me understand how to reach journalists without going through press agencies.

Perché i grandi nomi dell’architettura in Italia sono spesso uomini?

Le dinamiche di potere nell’architettura, che coinvolgono ingenti investimenti e relazioni politiche, si sviluppano spesso in contesti tradizionalmente maschili. Un simbolo di questa esclusività sono i vespasiani o pisciatoi collettivi, luoghi informali dove si consolidano connessioni e si prendono decisioni cruciali. Lo stesso vale per conversazioni su temi come calcio, automobili o barche, spazi che implicitamente escludono molte donne.

Fortunatamente, essendo la seconda figlia femmina di un ingegnere navale sommergibilista (per nulla macho) e successivamente progettista delle prime forme di intelligenza artificiale dell’Olivetti, ho ricevuto un’educazione atipica che mi ha formato in modo pratico e dinamico. Da ragazza correvo in Fortunatamente, essendo la seconda figlia femmina di un ingegnere navale sommergibilista (per nulla macho) e successivamente progettista delle prime forme di intelligenza artificiale dell’Olivetti, ho ricevuto un’educazione atipica che mi ha formato in modo pratico e dinamico. Da ragazza correvo in auto e moto, riparavo tubature con la fiamma ossidrica, guidavo barche e derive veloci e, grazie alla mia esperienza come ranger al Parco Nazionale delle Everglades, ho sviluppato un profilo trasversale.

Why are the big names in architecture in Italy often men?

Power dynamics in architecture, which involve significant investments and political relationships, often unfold in traditionally male-dominated contexts. A symbol of this exclusivity can be found in urinals or communal bathrooms—informal spaces where connections are forged and crucial decisions are made. The same applies to conversations about soccer, cars, or boats—arenas that implicitly exclude many women.

Fortunately, as the second daughter of a naval engineer specialising in submarines (and not at all macho) who later became a designer of early artificial intelligence systems for Olivetti, I received an unconventional upbringing that shaped me practically and dynamically. As a girl, I raced cars and motorcycles, repaired pipes with a blowtorch, piloted fast sailboats, and—thanks to my experience as a ranger at Everglades National Park—developed a well-rounded, hands-on skill set.

Power dynamics in architecture, which involve significant investments and political relationships, often unfold in traditionally male-dominated contexts. A symbol of this exclusivity can be found in urinals or communal bathrooms—informal spaces where connections are forged and crucial decisions are made. The same applies to conversations about soccer, cars, or boats—arenas that implicitly exclude many women.

Fortunately, as the second daughter of a naval engineer specialising in submarines (and not at all macho) who later became a designer of early artificial intelligence systems for Olivetti, I received an unconventional upbringing that shaped me practically and dynamically. As a girl, I raced cars and motorcycles, repaired pipes with a blowtorch, piloted fast sailboats, and—thanks to my experience as a ranger at Everglades National Park—developed a well-rounded, hands-on skill set.

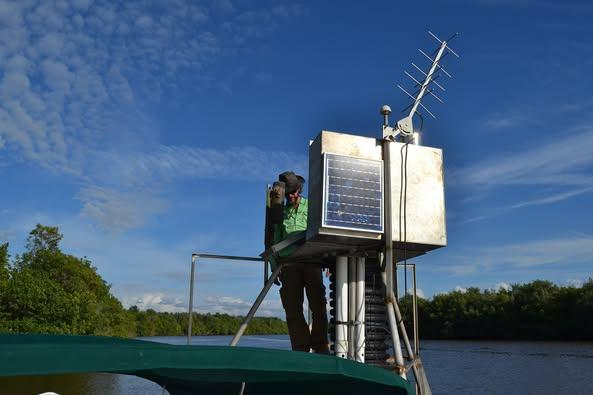

Fig.2: Visita con Scienziato Steven Tennis. Sopralluogo per la valutazione della proporzione ti acqua dolce e salata.

Fig.2: Visit with Scientist Steven Tennis—site inspection to evaluate the proportion of freshwater and saltwater.

Mi hai chiesto cosa mi ha dato la mia esperienza all’estero. Viaggi, strategie spaziali e culturali: un percorso tra esperienze e innovazione?

Le esperienze all’estero possono rappresentare un potente stimolo di crescita o, al contrario, condurre a una forma di decadenza. Lo so bene, provenendo da una famiglia apolide. La mia formazione scolastica è iniziata in una scuola statale francese, progettata per garantire ai figli di espatriati un’istruzione in linea con i programmi nazionali, con un focus scientifico nel mio caso.

Dopo il liceo, ho proseguito gli studi al Politecnico di Torino, partecipando negli anni ’90 al programma Erasmus a Valencia. In seguito, il mio percorso accademico ha preso una piega internazionale: un master alla Columbia University a New York si è affiancato a un dottorato in Italia, il tutto mentre lavoravo come progettista nel settore retail. Questo mix di esperienze ha nutrito una cultura pratica, digitale e intellettuale, in un’epoca in cui il di gitale iniziava a influenzare il design. Da qui è nata la mia proposta alla Columbia University con il Politecnico di Torino: creare la Non-Linear Solutions Unit (NSU), un’unità di ricerca che ho diretto per quindici anni, integrando realtà virtuale, intelligenza artificiale e progettazione del costruito.

Un interrogativo centrale per l’autrice è stato il rapporto tra soggettività e oggettività nei progetticreativi. Questa domanda ha guidato il suo lavoro e l’ha portata alSanta Fe Institute, un centro di ricerca interdisciplinare dove le scienze umane si uniscono alla tecnologia, rappresenta un luogo unico in cui le scienze umane si intrecciano con il pensiero dell’uomo e le tecnologie emergenti, tra cui una sorta di proto-intelligenza artificiale guidata dall’ingegno umano. Qui ho sviluppato la tecnica dellaCombinatorial Architecturepresentato alTEDxSalon, che gestisce valori soggettivi e oggettivi, materiali e immateriali.

You asked me what my experience abroad has given me. Travels, spatial and cultural strategies: a journey through experiences and innovation.

Experiences abroad can serve as a powerful catalyst for growth or, conversely, lead to a form of decline. I know this well, coming from a nomadic family. My education began in a French public school designed to provide expatriates’ children with a scientifically oriented curriculum aligned with national standards.

After high school, I continued my studies at the Polytechnic University of Turin, participating in the Erasmus program in Valencia during the 1990s. My academic journey then took an international turn: a master’s degree at Columbia University in New York was complemented by a PhD in Italy while working as a retail designer. This blend of experiences nurtured a practical, digital, and intellectual culture when digital technology began to shape design. This convergence inspired my proposal to Columbia University and the Polytechnic University of Turin to create the Non-Linear Solutions Unit (NSU), a research unit I directed for 15 years, integrating virtual reality, artificial intelligence, and built-environment design.

A central question in my work has been the relationship between subjectivity and objectivity in creative projects. This inquiry led me to the Santa Fe Institute, an interdisciplinary research centre where humanities meet technology. It is a unique place where human sciences intertwine with ingenuity and emerging technologies, including proto-artificial intelligence driven by human creativity. At the Santa Fe Institute, I developed the technique of Combinatorial Architecture, which I presented at TEDx Salon. This method manages subjective and objective values and material and immaterial dimensions, bringing them together into a cohesive framework.

Instant Installation

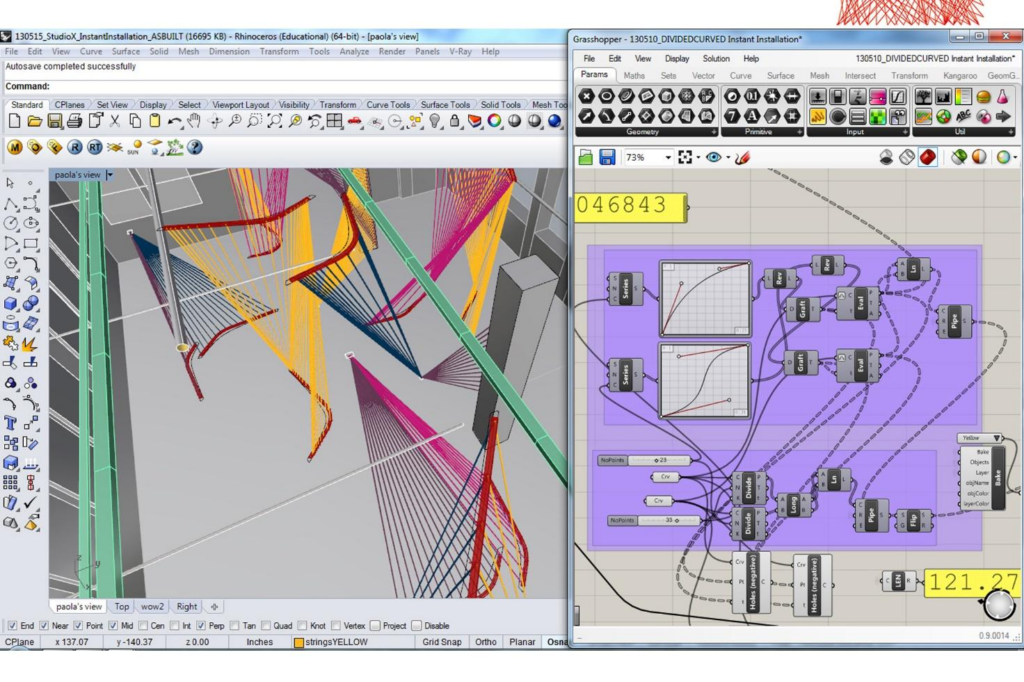

Il progetto Instant Installation rappresenta un’innovazione nel design parametrico, trasformando l’architettura tradizionale in un’esperienza interattiva e dinamica. Consiste in un labirinto flessibile di fili di gomma colorati, realizzato con software parametrici avanzati che hanno ottimizzato ogni fase progettuale grazie a un approccio algoritmico e l’uso di proto-intelligenza artificiale.

Il cuore del progetto è un sistema parametrico capace di apprendere dai vincoli del design e suggerire soluzioni spaziali innovative, adattandosi sia agli utenti che al contesto. Questo esempio dimostra l’interazione tra soggettività – visione estetica e concettuale – e oggettività, attraverso strumenti tecnologici che ampliano le possibilità creative.

Infine, si riflette sul rapporto culturale nel design, proponendo un approccio filosofico e adattabile che favorisca un dialogo tra progetto e contesti differenti.

E sulla base di avere la capacità di creare forme ma soprattutto metodologie capaci di adattarsi differenti necessità e condizioni.

Instant Installation

The “Instant Installation” project represents an innovation in parametric design, transforming traditional architecture into an interactive and dynamic experience. It consists of a flexible maze of colourful rubber threads, created with advanced parametric software that optimised every phase of the design process through an algorithmic approach and proto-artificial intelligence.

The heart of the project is a parametric system capable of learning from the design constraints and suggesting innovative spatial solutions, adapting to both users and the context. This example demonstrates the interaction between subjectivity—aesthetic and conceptual vision—and objectivity through technological tools that expand creative possibilities.

Finally, the project reflects on the cultural relationship in design, proposing a philosophical and adaptable approach fostering a dialogue between the project and different contexts.

Based on the ability to create forms, but especially methodologies capable of adapting to different needs and conditions.

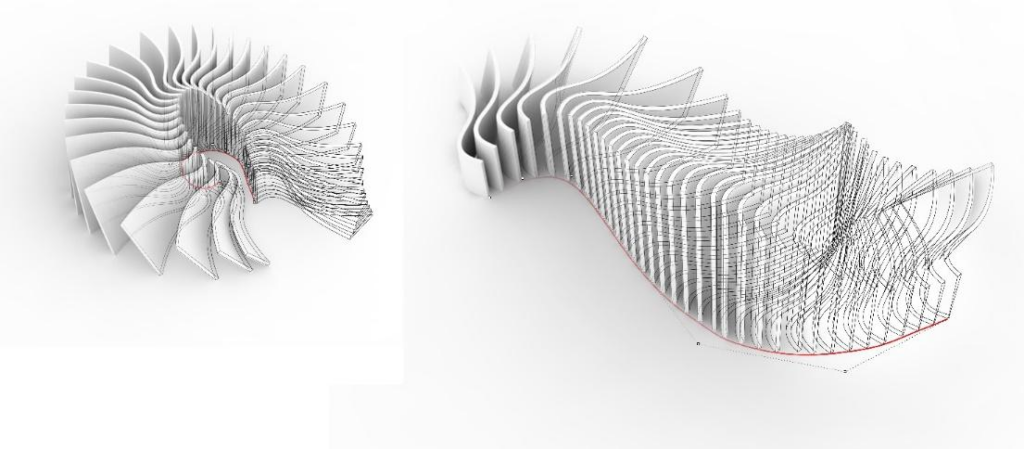

Fig.3: Flessibilità e plasmabilità dei degli spazi pesi e colori. Grazie alla sua flessibilità questa installazione ha viaggiato in molti paesi, è stata presentata alla Galleria di Arte Moderna di Torno, nonché all’Area Educativa del Castello di Rivoli

Fig.3: Flexibility and adaptability of spaces, weights, and colours. Thanks to its flexibility, this installation has travelled to many countries. It has been showcased at the Gallery of Modern Art in Torino and in the Educational Area of the Rivoli Castle.

Fig.4: Famiglie di forme che possano adattarsi velocemente, dal parco pubblico nel Bronx, alla super villa per milionari.

Fig.4: Families of forms that can quickly adapt, from the public park in the Bronx to the luxury mansion for millionaires.

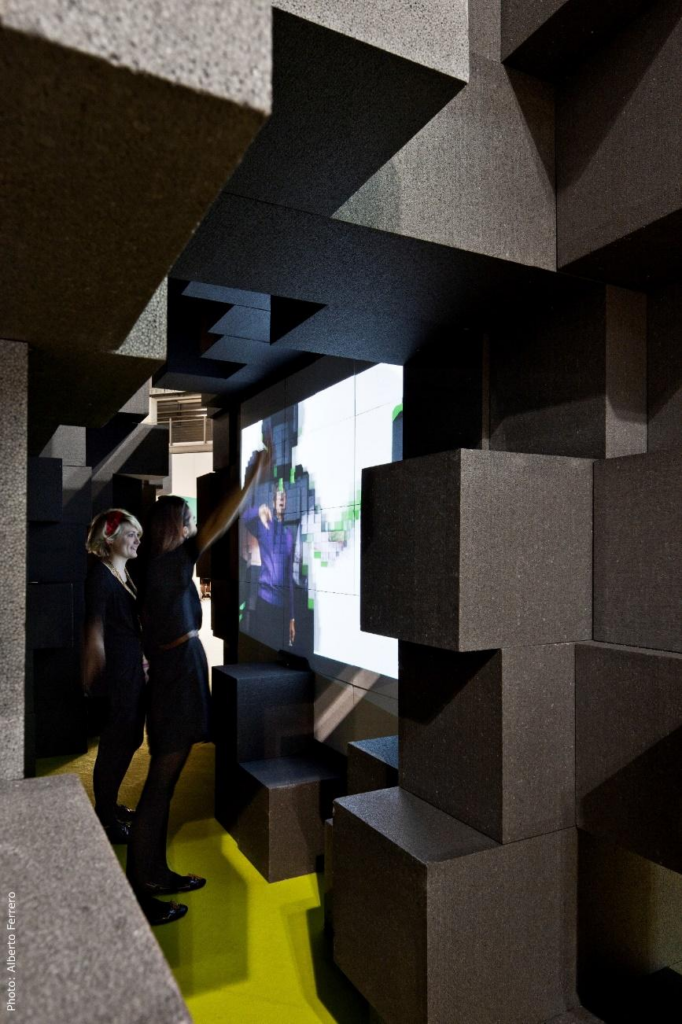

The Social Cave Social Cave

Con la crescente connettività virtuale abbiamo a disposizione una rete di percorsi di comunicazione illimitati. Tuttavia, se da un lato la nostra “capacità sociale” è aumentata, spesso le relazioni generate dal web rimangono confinate allo spazio digitale in cui sono nate.

Con la fusione dello spazio fisico e virtuale, in che modo il design può creare un nuovo tipo di interazione?

Su questo tema, la Facoltà di Architettura della Columbia University ha ideato Social Cave, la grotta sociale, una piccola installazione interattiva “che torna alle origini della nostra civiltà”, come spiegano i creatori. È un aggregato parametrico di cubi di polistirolo riciclati e riciclabili al 100%. All’interno, Social Cave ha due spazi separati da un muro con due entrate distinte. La presenza di persone dall’altra parte è svelata solo tramite una proiezione astratta sul muro. I visitatori possono osservare movimenti, posture e comunicazione non verbale degli altri. L’anonimato fisico è garantito dal muro e dall’astrazione dell’immagine, favorendo conversazioni digitali e visive con le “ombre” dei visitatori di fronte, abbattendo barriere inibitorie.

Once you leave the Social Cave, you return to physical reality, where you can continue the connection. The social cave hides and then reveals visitors’ proximity and identity, allowing conversations to begin that transcend the physical limits of digital communication.

The Social Cave Social Cave

With the growing virtual connectivity, we now have an unlimited network of communication pathways. However, while our “social capacity” has increased, the relationships generated by the web often remain confined to the digital space in which they were born.

With the fusion of physical and virtual space, how can design create a new type of interaction?

The Columbia University School of Architecture developed Social Cave on this theme, a small interactive installation “that returns to the origins of our civilisation,” as the creators explain. It is a parametric aggregation of recycled and 100% recyclable Styrofoam cubes. Inside, Social Cave features two spaces separated by a wall with two distinct entrances. The presence of people on the other side is revealed only through an abstract projection on the wall. Visitors can observe movements, postures, and non-verbal communication of others. Physical anonymity is ensured by the wall and the abstraction of the image, encouraging digital and visual conversations with the “shadows” of the visitors across from them and breaking down inhibitive barriers.

Fig.5: Il corridoio che divide le due parti

Fig. 5: The corridor that divides the two parts

Fig.6: A più di un metro dalla telecamera, la persona si vede come se fosse in uno specchio pixellato.

Fig.6: More than a meter away from the camera, the person appears as if in a pixelated mirror.

Fig.7: A meno di un metro dalla telecamera si apre una porta digitale e si intravede chi sta dall’altra parte.

Fig.7: A digital door opens less than a meter from the camera, and one can see the person on the other side.

Fig.8: I buchi presenti nella struttura fanno capire che le persone apparentemente virtuali che si muovono, sono esseri umani veri.

Fig. 8: The holes in the structure make it clear that the seemingly virtual beings moving around are real human beings.

Una volta usciti dalla Social Cave, si torna nella realtà fisica, dove si può proseguire la conoscenza. La grotta sociale nasconde e poi svela vicinanza e identità dei visitatori, permettendo di iniziare conversazioni che superano i limiti fisici della comunicazione digitale.

Once you leave the Social Cave, you return to physical reality, where you can continue the connection. The social cave hides and then reveals visitors’ proximity and identity, allowing conversations to begin that transcend the physical limits of digital communication.

Il negozio Illy Shop

Arredato esclusivamente con cubi bianchi, dimensionati esattamente per contenere barattoli di caffè e macchine per espresso. Anche il bancone, il tavolo per le degustazioni e i cestini per i rifiuti sono realizzati con questi cubi, così come le luci fissate al soffitto.

The Illy Shop.

Illy Soph is furnished exclusively with white cubes, precisely sized to hold coffee cans and espresso machines. These cubes also make the counter, the tasting table, the wastebaskets, and the lights fixed to the ceiling.

Fig. 10 Vetrina inquadramento chiaro simmetrico quasi giocosa

Fig. 10 Showcase with a precise, symmetrical, almost playful framing.

Fig.11: angolo sensoriale, degustazione di impronta user friendly

Fig. 11: Sensory corner, user-friendly tasting experience

Fig. 12: un’immagine fatta per stupire, per disorientare e per fare girare il nome del brand.

Fig. 12: An image that amazes, disorients, and makes the brand’s name go viral.

Toolbox: Un Coworking e Incubatore per la Rigenerazione Urbana

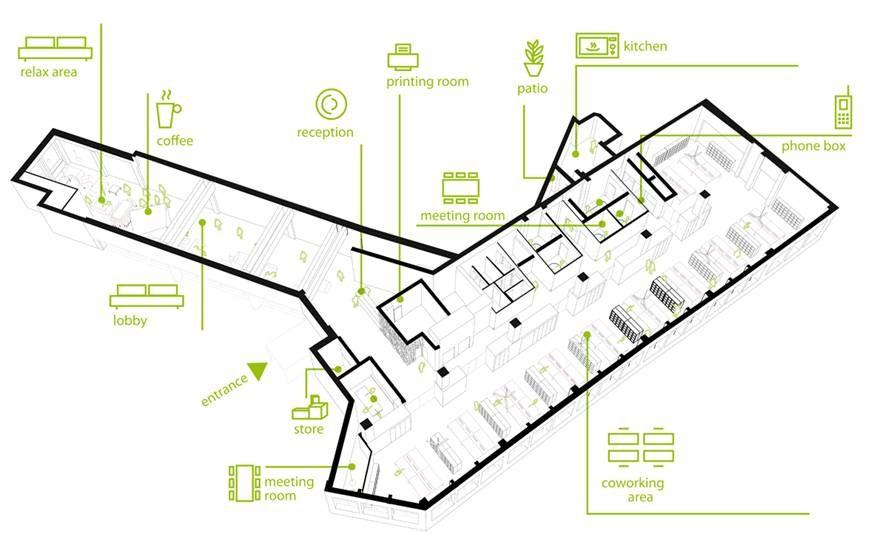

Applicando la stessa metodologia Toolbox Coworking a Torino, è un progetto che mi ha portata a essere finalista al Premio Renzo Piano per un giovane talento italiano, ho collaborato con Giulio Milanese e Aurelio Balestra per sviluppare un brief, una bozza di piano di sviluppo futuro e realizzare i primi 2000 mq di questo innovativo spazio.

Situato in un ex edificio industriale, Toolbox risponde alle esigenze di una città in evoluzione. In un’epoca in cui si può lavorare ovunque con un laptop e Wi-Fi, il progetto riflette sul ruolo degli spazi professionali, bilanciando socializzazione, privacy, relax e concentrazione. Prevede un openspace con 44 postazioni, spazi comuni e una struttura modulare in cemento. I “volumi filtro” separano le aree operative e funzionali. Basato sulla Componente Adattabile di Tiazzoldi, il design utilizza volumi identici con variazioni di materiali e finiture per esigenze acustiche e visive. Software parametrici hanno creato 500 varianti di pareti e pavimenti in gomma colorata.

Toolbox: A Coworking Space and Incubator for Urban Regeneration Link

Applying the same Toolbox Coworking methodology in Turin, a project that led me to become a finalist for the Renzo Piano Award for young Italian talent, I collaborated with Giulio Milanese and Aurelio Balestra to develop a brief, draft a future development plan, and create the first 2,000 sqm of this innovative space.

Located in a former industrial building, Toolbox meets the needs of a city in evolution. In an era where one can work anywhere with a laptop and Wi-Fi, the project reflects on the role of professional spaces, balancing socialisation and privacy, relaxation and focus. The design features an open space with 44 workstations, common areas, and a modular concrete structure. “Filter volumes” separate operational and functional areas. Based on my Adaptable Components Methodology, the design uses identical volumes with variations in materials and finishes to address acoustic and visual needs. Parametric software produced 500 variations of walls and coloured rubber flooring.

..

Il progetto crea spazi che stimolano interazioni spontanee. Un esempio è la zona bar, progettata per essere stretta, favorendo l’interazione fisica. Dietro il bar, un bancone in piastrelle e giornali incoraggia chiacchiere informali. Più avanti, un salottino accogliente offre un ambiente rilassato per brainstorming e collaborazioni, mentre il bancone diventa un luogo per lavorare su bozze di contratti, senza il formalismo di una sala riunioni.

In questo modo, il progetto trasforma l’interazione in un’esperienza naturale e fluida.

The project creates spaces that stimulate spontaneous interactions. One example is the bar area, which is designed to be narrow and encourage physical interaction. Behind the bar, a counter made of tiles and newspapers fosters informal conversations. Further ahead, a cosy lounge offers a relaxed environment for brainstorming and collaboration. At the same time, the counter becomes a place to work on contract drafts, free from the formality of a meeting room.

In this way, the project transforms interaction into a natural and fluid experience.

Fig.13: Vista de bar strettoia arancione, bancone informale per i primi incontri, sala riunione.

Fig13: View of the narrow orange bar, informal counter for first meetings, and meeting room.

Mi chiedi dell’accessibilità? L’accessibilità è cruciale.

Negli ultimi vent’anni, in Italia, sono stati fatti passi avanti per migliorare la mobilità delle persone con disabilità. Tuttavia, la conformazione naturale del Paese ha sempre reso la mobilità complicata.

Questa realtà non giustifica ritardi o mancanza di sensibilità verso il tema. Lo storico Fernand Braudel, nel suo libro Mare Nostrum, descrive l’Italia come un Paese difficile da attraversare, con coste impervie e montagne, ma quasi inespugnabile.

Queste caratteristiche hanno influenzato la progettazione delle città, molte inadatte alla mobilità moderna. Paesi più accessibili beneficiano di una geografia più favorevole. Questo dovrebbe spingere a trovare soluzioni innovative e pratiche.

In Italia ci sono margini di miglioramento. Interventi come una gestione razionale degli spazi urbani e corsie stradali meglio dimensionate potrebbero fare la differenza. A New York, dove ho vissuto, le strette strade di Soho sono organizzate con linee gialle che danno priorità a biciclette, rollerblade e carrozzine, facilitando la convivenza tra pedoni e mezzi. Inoltre, le telecamere monitorano il rispetto delle regole con sanzioni severe.

Un approccio che unisce organizzazione e rigore normativo dimostra che anche contesti complessi possono migliorare l’accessibilità. Non serve rivoluzionare l’Italia, ma migliorarla gradualmente, rispettando il suo patrimonio culturale e favorendo l’inclusione.

You’re asking me about accessibility? Accessibility is crucial. In the last twenty years, progress has been made in Italy to improve the mobility of people with disabilities. However, the country’s natural layout has always made mobility complicated.

This reality does not justify delays or a lack of sensitivity. In his book Mare Nostrum, the historian Fernand Braudel describes Italy as a country challenging to cross, with rugged coastlines and mountains, but almost impregnable.

These characteristics have influenced the design of cities, many of which are unsuitable for modern mobility. More accessible countries benefit from more favourable geography. This should drive us to find innovative and practical solutions.

In Italy, there is room for improvement. Interventions like rational management of urban spaces and better-sized road lanes could make a difference. In New York, where I lived, the narrow streets of Soho are organised with yellow lines prioritising bicycles, rollerblades, and wheelchairs, facilitating coexistence between pedestrians and vehicles. Additionally, cameras monitor adherence to rules with strict penalties.

An approach that combines organisation and regulatory rigour demonstrates that even complex contexts can improve accessibility. Italy does not need to revolutionize; it should be improved gradually, respecting its cultural